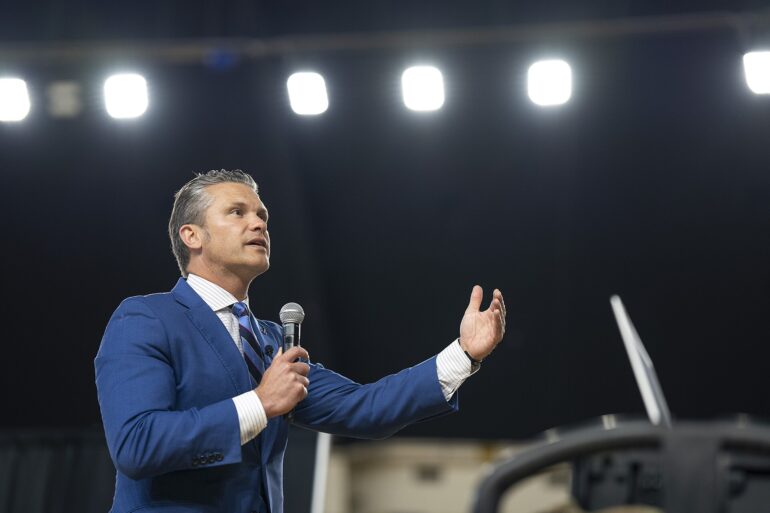

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth on Monday openly mocked major media outlets after they announced they would not comply with the Pentagon’s new press-access policy, responding to several statements with a simple goodbye handwave emoji.

The Associated Press, Reuters, The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Atlantic, CNN and NPR all declared that their reporters would not sign the Pentagon’s new paperwork, which requires acknowledgment of tightened rules governing access to Defense Department officials and facilities. The outlets posted their refusals on social media, framing the policy as a threat to press freedom.

Hegseth, who has long criticized what he views as a politically biased and unaccountable press corps, appeared unbothered. When The Atlantic wrote that it “fundamentally opposes” the restrictions, the defense secretary replied with the waving-hand emoji. He did the same to The Washington Post, which claimed the rules undercut the First Amendment, and to The New York Times, which accused the Pentagon of seeking to punish journalists for “ordinary news gathering.”

The dismissive replies drew outrage from reporters but underscored Hegseth’s willingness to confront legacy media institutions that have historically shaped public perceptions of the U.S. military. Supporters of the policy argue that the Pentagon has every right to set clear guidelines for access, particularly at a time of heightened global tensions and national security risks.

Hegseth’s approach marks a stark break from decades of looser Pentagon access. Earlier this year, his office reassigned workspace privileges in the Pentagon press corridor, replacing outlets such as Reuters and The Hill with news organizations that have offered more balanced or administration-friendly coverage, including One America News Network and Breitbart News.

While reporters who lost their desks were still allowed to enter the building, officials also tightened access to the Pentagon briefing room — one of the few areas with reliable wireless internet.

In May, Hegseth further restricted journalists from walking unescorted through much of the building, a move critics described as heavy-handed but which supporters said was consistent with security procedures in other federal agencies.

Under the new policy, reporters are not formally prohibited from investigating or publishing stories about the U.S. military. However, those who solicit information deemed sensitive — even if unclassified — could be labeled a “security or safety risk,” according to a draft of the rules.

The Pentagon defines “solicitation” broadly, encompassing requests for tips or encouragement of personnel to share nonpublic information.

Routine press briefings, once a hallmark of Pentagon transparency, have largely disappeared in recent months. The Pentagon Press Association accused Hegseth’s team last week of “systematically limiting access to information about the U.S. military,” a claim Hegseth’s aides dispute, citing national security concerns and a need to reduce leaks.

Even some conservative-leaning outlets have hesitated to endorse the changes. The Washington Times and Newsmax both said they would not sign, with Newsmax calling the new requirements “unnecessary and onerous.” Still, Hegseth’s allies argue that most Americans support efforts to protect military operations from political spin or leaks that could compromise safety.

Beat reporters have until Tuesday to sign the agreement or surrender their Pentagon credentials by Wednesday. Editors from the affected outlets have vowed to continue covering defense and national security, with or without access.

For Hegseth, a former Army officer and Fox News contributor known for his blunt manner, the confrontation reflects a broader struggle over accountability and trust between the Pentagon and the press. His critics call it censorship. His defenders call it long-overdue reform. Either way, the standoff underscores a shifting media landscape in Washington — one where the Pentagon, not the press, appears increasingly in control of the message.

[READ MORE: Oregon to Spend More on Health Care for Illegal Immigrants Than on State Police]